American Chestnut

American Chestnut

Castanea dentata

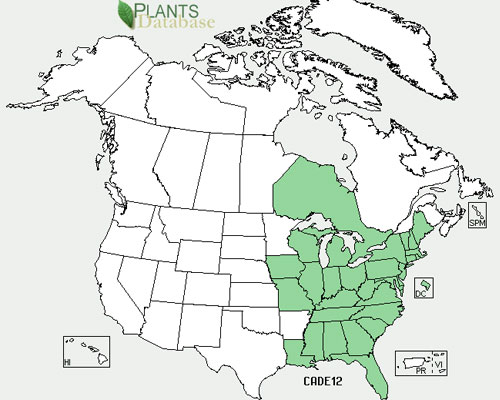

The American chestnut was one of the most important dominant forest trees of eastern North America prior to 1930. The nuts, sweet and edible, were a favorite confection in the eastern United States. The wood is light, strong, and resistant to decay; it was widely used for construction, furniture, and decorative trim. The bark was used for tanning leather. Native Americans used various parts of the plants of Castanea dentata medicinally as a cough syrup and to treat whooping cough, for heart trouble, and as a powder for chafed skin (D. E. Moerman 1986). https://www.efloras.org/florataxon

The following is from the American Chestnut Restoration Project website (https://www.fs.fed.us/r8/chestnut/index.php). The U.S. Forest Service, The American Chestnut Foundation, and the University of Tennessee have been conducting research and tests to produce a blight-resistant American chestnut, with aspirations of restoring the species.

What Once Was a Mighty Tree

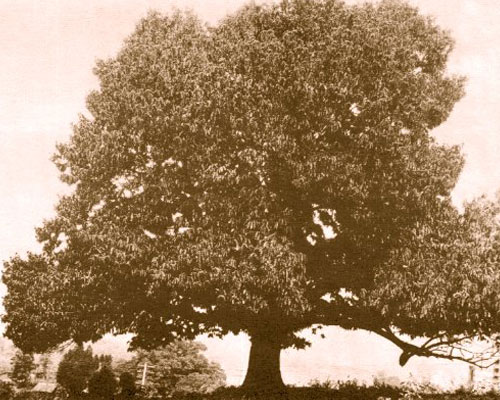

The American chestnut tree stood majestic across some 200 million acres of eastern woodlands, from Maine to Florida and westward to the Ohio Valley. It grew straight and tall, like a Mighty Giant, and was an integral part of culture and commerce for Appalachian people.

During the first half of the 20th century, a lethal fungus—the chestnut blight—infected the species. It was first discovered in 1904 in New York City, but quickly spread throughout the country. About four billion American chestnut trees, literally a quarter of the hardwood tree population of the East, were destroyed.

The blight arrived in the United States on chestnut trees imported from Asia. Spores spread the disease traveling through the air, in raindrops, and also by hitching a ride in the fur of mice, squirrels, and rabbits that used the trees for food and shelter. A spore would settle into a wound in the bark, allowing the disease to spread quickly to the wood. Native chestnuts, although mighty trees, had very little resistance. Once infected, their leaves would die off during the first season and the whole tree typically would be dead by year two.

Dead and damaged trunks of giant trees were left behind like skeletons. The New York Times wrote about the doomed chestnut tree. Ghosts of the giant trees littered the landscape. Foresters investigated, but were unable to stop the fungus from spreading. By 1950 the live species had virtually disappeared.

In its majesty, the American chestnut tree was admired for its beauty and protection. The tree was also prized for lumber. It grew straight and tall, often shooting up 50 feet before branching out. The wood weighed less than oak but resisted rot as well as redwood. Its straight grain made it favorable for woodworking and all sorts of wood products—fine furniture, musical instruments, railroad ties, shingles, paneling, telephone poles, even pulp and plywood. Chestnut wood was used from cradle to coffin.

Americans paid homage to the chestnut tree in poetry, paintings, newspapers, and books. Even its nut was popular. The song lyric “chestnuts roasting on an open fire” is reminiscent of how common yet comforting the chestnut was in America.

American chestnut was a keystone species in the eastern hardwood forests, and its demise has altered forest ecosystems by reducing species diversity, reducing availability of hard mast, and changed soil and litter dynamics. The loss of the American chestnut as a mature component in eastern forests has resulted in large-scale shifts in species composition, particularly on upland well-drained stands where the species was most competitive. Because the chestnut blight affects only the above-ground portion of the tree, the species has managed to exist as short-lived stump and root sprouts, which will occasionally live long enough to flower and bear fruit.

Restoration of American chestnut to eastern forests depends on the development of blight-resistant seedlings. The Forest Service does not conduct breeding research, but supports efforts of The American Chestnut Foundation (TACF), a private non-profit organization whose goal is to produce blight-resistant chestnut trees through a back-cross breeding program involving the blight-resistant Chinese chestnut (Castanea mollissima Blume). The TACF breeding program's end product is essentially an American chestnut with blight resistance from Chinese chestnut.

Chestnut restoration does not end with development of a blight-resistant tree, but also requires a prescription for how and where to plant trees once available. To date, planning for American chestnut restoration has emphasized producing a blight-resistant tree, and only limited attention and resources have been specifically given to test procedures needed for successful establishment and growth of resistant seedlings.